Welcome to the third installment of The Long(ish) Read: an AD feature which uncovers texts written by notable essayists that resonate with contemporary architecture, interior architecture, urbanism or landscape design. In this extract from The Seven Lamps of Architecture, published in 1849 and considered to be John Ruskin's first complete book on architecture, his studies are distilled into seven moral principles. These "Lamps" were intended to guide architectural practice of the time, advocating a profound respect for the original fabric of existing buildings. The opening chapter—The Lamp of Sacrifice—attempts to "distinguish carefully between Architecture and Building," set against the backdrop of Ruskin's (often criticised) world-view on the discipline at large.

John Ruskin in brief

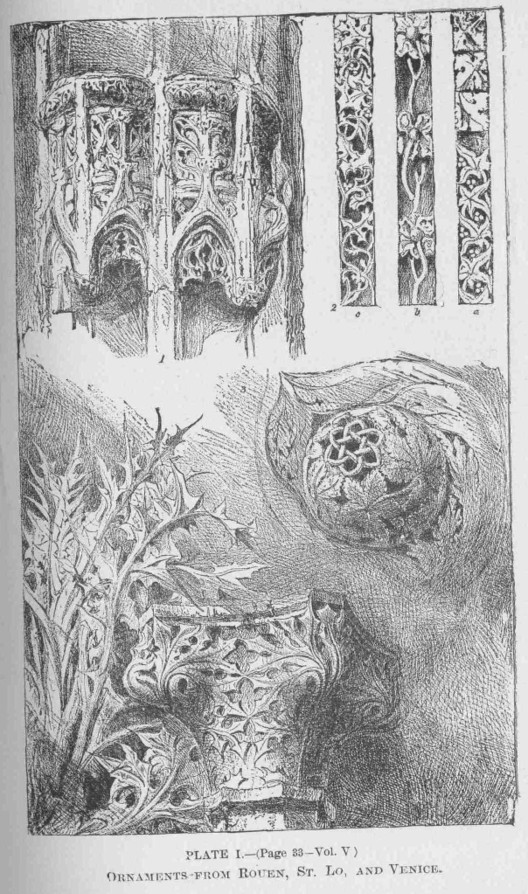

Born in London in 1819, Ruskin was an art, architecture and society critic who, throughout his eighty-one year life, painted, wrote and campaigned for (widespread) societal change. Although not an architect himself, he lived through the height of the British Empire with Queen Victoria at its helm, and helped to pioneer the proliferation of the Romantic and Gothic Revival movements in England. He would later write The Stones of Venice (1851–53), for which he is most well known.

Extract from the beginning of Chapter One: The Lamp of Sacrifice

I. Architecture is the art which so disposes and adorns the edifices raised by man for whatsoever uses, that the sight of them contributes to his mental health, power and pleasure.

It is very necessary, in the outset of all inquiry, to distinguish carefully between Architecture and Building.

To build, literally to confirm, is by common understanding to put together and adjust the several pieces of any edifice or receptacle of a considerable size. Thus we have church building, house building, ship building, and coach building. That one edifice stands, another floats, and another is suspended on iron springs, makes no difference in the nature of the art, if so it may be called, of building or edification. The persons who profess that art, are severally builders, ecclesiastical, naval, or of whatever other name their work may justify; but building does not become architecture merely by the stability of what it erects; and it is no more architecture which raises a church, or which fits it to receive and contain with comfort a required number of persons occupied in certain religious offices, than it is architecture which makes a carriage commodious or a ship swift. I do not, of course, mean that the word is not often, or even may not be legitimately, applied in such a sense (as we speak of naval architecture); but in that sense architecture ceases to be one of the fine arts, and it is therefore better not to run the risk, by loose nomenclature, of the confusion which would arise, and has often arisen, from extending principles which belong altogether to building, into the sphere of architecture proper.

Let us, therefore, at once confine the name to that art which, taking up and admitting, as conditions of its working, the necessities and common uses of the building, impresses on its form certain characters venerable or beautiful, but otherwise unnecessary. Thus, I suppose, no one would call the laws architectural which determine the height of a breastwork or the position of a bastion. But if to the stone facing of that bastion be added an unnecessary feature, as a cable moulding, that is Architecture. It would be similarly unreasonable to call battlements or machicolations architectural features, so long as they consist only of an advanced gallery supported on projecting masses, with open intervals beneath for offence. But if these projecting masses be carved beneath into rounded courses, which are useless, and if the headings of the intervals be arched and trefoiled, which is useless, that is Architecture. It may not be always easy to draw the line so sharply and simply, because there are few buildings which have not some pretence or color of being architectural; neither can there be any architecture which is not based on building, nor any good architecture which is not based on good building; but it is perfectly easy and very necessary to keep the ideas distinct, and to understand fully that Architecture concerns itself only with those characters of an edifice which are above and beyond its common use. I say common; because a building raised to the honor of God, or in memory of men, has surely a use to which its architectural adornment fits it; but not a use which limits, by any inevitable necessities, its plan or details.

II. Architecture proper, then, naturally arranges itself under five heads:—

- Devotional; including all buildings raised for God's service or honor.

- Memorial; including both monuments and tombs.

- Civil; including every edifice raised by nations or societies, for purposes of common business or pleasure.

- Military; including all private and public architecture of defence.

- Domestic; including every rank and kind of dwelling-place.

Now, of the principles which I would endeavor to develop, while all must be, as I have said, applicable to every stage and style of the art, some, and especially those which are exciting rather than directing, have necessarily fuller reference to one kind of building than another; and among these I would place first that spirit which, having influence in all, has nevertheless such especial reference to devotional and memorial architecture—the spirit which offers for such work precious things simply because they are precious; not as being necessary to the building, but as an offering, surrendering, and sacrifice of what is to ourselves desirable. It seems to me, not only that this feeling is in most cases wholly wanting in those who forward the devotional buildings of the present day; but that it would even be regarded as an ignorant, dangerous, or perhaps criminal principle by many among us. I have not space to enter into dispute of all the various objections which may be urged against it—they are many and spacious; but I may, perhaps, ask the reader's patience while I set down those simple reasons which cause me to believe it a good and just feeling, and as well-pleasing to God and honorable in men, as it is beyond all dispute necessary to the production of any great work in the kind with which we are at present concerned.

Read The Seven Lamps of Architecture on Project Gutenberg.